Opinion by Leonardo Badea, Deputy Governor of the National Bank of Romania (BNR)

“Consolidating Romania’s external economic balance is an important concern from the perspective of the dynamics of structural factors, but also of the effects of overlapping crises manifested in recent years, which have contributed to maintaining a high level of trade and current account deficits. Therefore, beyond the analysis of short-term fluctuations of the relevant indicators, it is useful to have a perspective of Romania’s strategic positioning in the region, as a participant in international trade flows and as a destination for foreign direct investments.

As globalization continues to redefine the dynamics of international trade and investment, re-examining the strategic positioning of the country’s economy in these areas is relevant to shaping future economic prospects and strategic partnerships.

The current place and role of the Romanian economy within international trade and investment flows resulted from a complex interaction of historical developments, geopolitical factors, and internal economic policy decisions. In recent years, the economic development of the country has been mainly influenced by the efforts to counteract the negative effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Comparing Romania’s economic position on the external front with that of the relevant economies in the region, we could identify a series of steps to improve the current situation.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of Romania’s economic position in global trade and financial markets, it is essential to study its performance relative to comparable economies, with countries often included in such analyzes including Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Each of these nations shares a similar history since the early 1990s of transition from communism to market-based economies, albeit at different speeds, and currently compete for foreign investment and trade opportunities in the region.

In the case of Romania, one of the key structural challenges is the still high share in total exports of those coming from industrial sectors characterized by low added value. Although steps have been taken in the development of the technology and services sectors, the external balance remains affected by lower competitiveness in the agri-food sector and that of products with a high technological level. Dependence on traditional industries contributes to the trade deficit, as Romania imports a significant amount of goods to meet domestic demand. Not only the growing consumption of households is offset by imported goods, but also the recent upward dynamics of investments (financed including by financial flows of foreign direct investments) was accompanied by the increase in imports (hypothesis supported not only at theoretical/conceptual level, but also through the statistical analysis of the annual variations of the values of the two indicators, resulting in some positive and statistically significant coefficients).

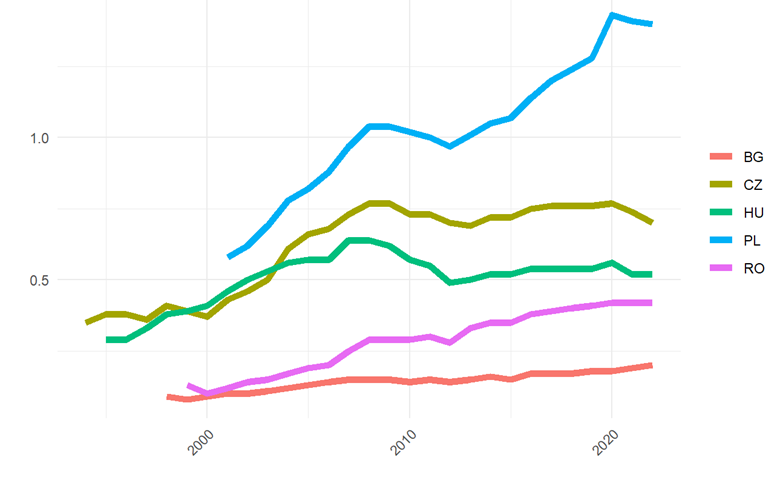

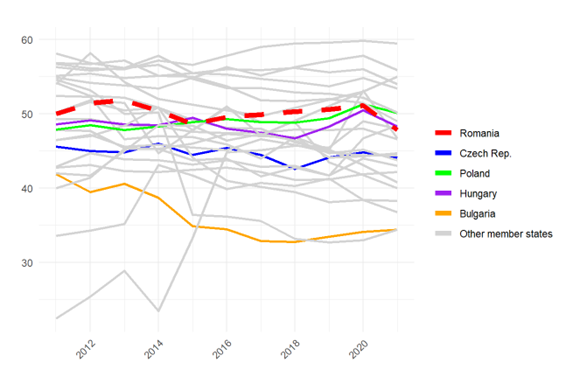

The data published by Eurostat show that during the last 20 years the market share of Romanian exports in international trade with goods and services has increased significantly, but has remained at one of the lowest levels compared to the countries in the area. The graph below shows that Poland recorded the most important market share gain in the mentioned period, its upward evolution being halted only during the peak years of the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis in Europe, and later during the pandemic period. Romania in turn recorded an important advance in relative terms, starting from a much smaller base, but, for more than 20 years, it did not gain a single position in the regional ranking, even though Hungary and the Czech Republic had their evolution practically capped after 2007. Thus, the market share of Romanian exports has significantly distanced itself from that of Bulgaria, which recorded a much slower progress and approached that of Hungary, but without surpassing it for the time being.

Figure 1: The evolution of the market share in international trade with goods and services

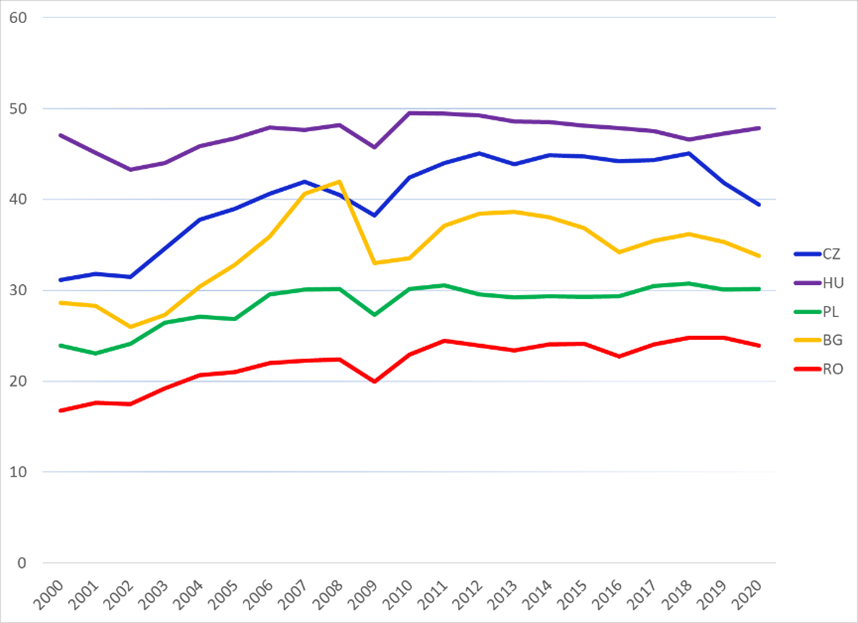

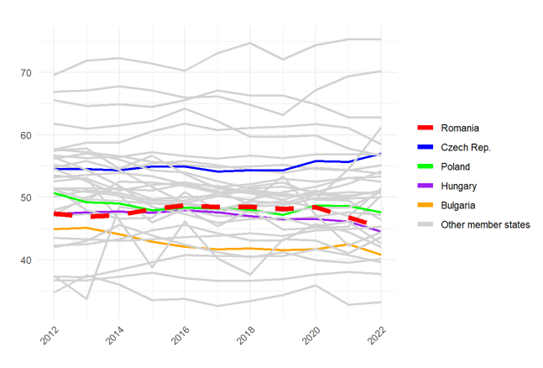

Figure 2: Import content of exports (%)

Although in 2020 Romania had a higher share of imports used in the production of exports compared to the average of the European Union (23.9% in Romania in contrast to the 15.9% EU average), regionally, during the past 10 years, we held more favorable positions compared to neighboring countries (for example, in 2020 this percentage was 30.1% in Poland, 39.4% in the Czech Republic, and 47.9% in Hungary – see Figure 2). However, for now, Romania does not manage to fundamentally improve the level of added value of domestic production processes in such a way as to improve the dependence of exports on imports within the categories of goods with a medium and high degree of complexity. These figures contradict the opinion that Romanian exports are based to a large extent on imports, an opinion that has circulated quite a lot recently. So, according to these data, the hypothesis that greater export stimulation would lead to a significant increase in imports cannot be confirmed, showing that, in fact, exports, even in the current structure, have a much more beneficial contribution to the macroeconomic balance, and efforts to increase them would bring an improvement in the external imbalance from multiple perspectives. Also, the mentioned data underline the fact that most imports are determined by internal consumption demand, but also by investments, which still exceed the capacity of the internal supply.

There is no doubt that investments are crucial for overcoming the effects of the current crises and for the future sustainable growth of the economy, but it is important to note that, for now, this involves significant imports of goods and services. At the same time, a positive fact is that the source of financing for an important part of these investments is ensured through European programs (non-reimbursable funds or loans with more advantageous cost conditions compared to those that Romania could have obtained directly), but it would be beneficial to accomplish them in a larger proportion based on goods and technologies produced in Romania.

For this, as a strategic choice, the focus must be on investing in the development of domestic capacity to produce goods with high technological content, which would reduce the dependence of future investments on imports and help correct the current external imbalances. At the same time, the spearhead of investments with a favorable impact on the Romanian economy must be the development by local companies of competitive technologies, which can be achieved by supporting research and development activities of private companies through coherent and consistent policies, correlated and synchronized with the research conducted by universities and public institutes.

It is useful to note that the ratio of exports to imports does not only depend on the dynamics of external demand and the balance between domestic consumption demand and the ability of domestic supply to cover it in a competitive manner (influenced by the wider economic policy framework). It is also influenced in a significant proportion by structural factors (of a commercial, logistical, and technological nature), related to domestic production intended for foreign markets.

Thus, apart from the exports of goods and merchandise from the categories of basic metals, agri-food, mineral and chemical products, as well as plastics, for which the raw materials are in a significant proportion obtained domestically, in the case of many of the other categories, the exports depend significantly on imports of components and intermediate products. At the same time, products from the machinery, equipment, and means of transport category, which have the most important share in the structure of exports, are still based on the use in a large proportion of imported raw materials, components, and subassemblies, the level of domestically added value being below potential.

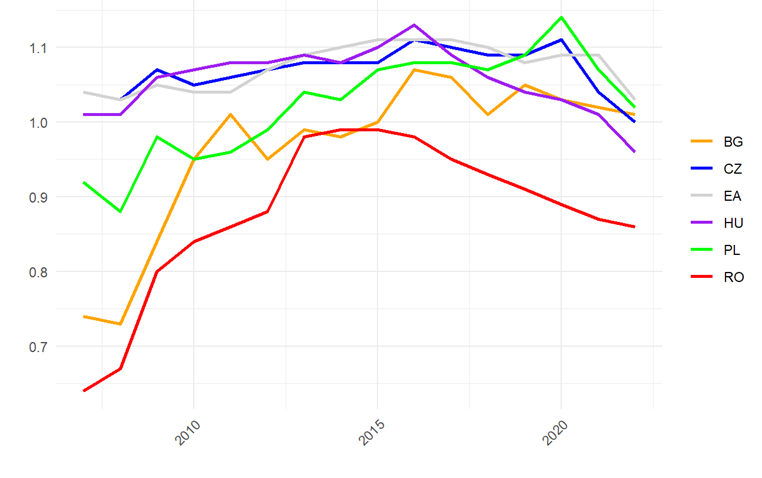

Figure 3 below shows that before 2005, Romania held the most unfavorable position in the region in terms of the ratio between exports and imports, but it quickly recovered the major gap compared to neighboring economies, so that in 2014-2015 the trade deficit was very small in percentage terms. All this time, however, the Czech Republic and Hungary recorded trade surpluses, with Poland joining this group after 2012.

Figure 3: The ratio between the value of exports and imports

After 2015, the ratio between exports and imports deteriorated significantly, noticeably faster compared to the countries in the region, which, with the exception of Hungary, maintained a trade surplus. During 2022, the largest deficits in Romania’s international trade were recorded in the category of chemical and plastic products (8.4 billion euros of which 7.3 billion in chemical products, especially medicine and care products) and mineral products (6.2 billion euros, reflecting, in particular, imports of crude oil). The largest surpluses were recorded in the category of machines, appliances, equipment and means of transport (1 billion euros), and wood products, paper ( 0.7 billion euros). Almost all service sub-sectors registered a trade surplus, by far the highest being in the case of telecommunications, IT, and information services, of approximately 5.7 billion euros (the report “Foreign direct investments in Romania in 2022” – available online on the website https://www.bnr.ro/Publicatii-periodice-204.aspx).

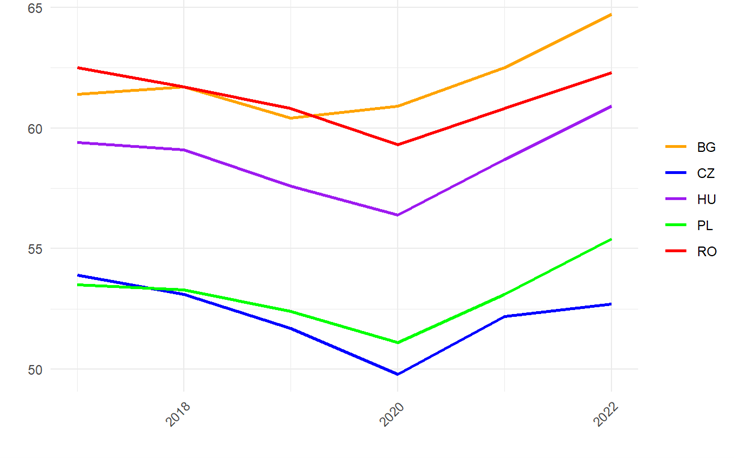

An important factor for the unfavorable evolution was the significantly higher budget deficit recorded in Romania compared to neighboring countries, but structural factors played also an important role. This last statement is supported by the overview provided by Figure 4 below, which shows that Romania recorded, during the entire period 2015-2022, one of the highest shares of the value of transactions with intermediate products compared to that of international trade with goods (imports + exports), being exceeded only by Bulgaria.

Figure 4: Share of intermediary goods transactions in the trade with goods

Looking at the graphs presented above from a different perspective, it can be stated that the loss of competitiveness of Romanian exports of goods and services is not the main cause of Romania’s current trade deficit. We have seen that the market share in international trade improved between 2000 and 2020, and after the outbreak of the pandemic crisis, it was maintained. Instead, it results, in large part, from structural causes closely related to the domestic supply, as well as from the influence of the economic policy mix on the balance between domestic supply and demand.

It is also useful to note that the diversification of Romania’s international commercial partners has been maintained over the last 10 years at a level comparable to that of the other member countries of the European Union, including the neighboring ones. Figure 5 below shows that the share of transactions with the top 5 partner countries in foreign trade is marginally lower than in the case of the Czech Republic or Poland, as well as most of the other member states. The overwhelming share of transactions with partners from single market member states is natural, and within these limits, the dependence on a small number of partner countries is no greater than in other economies in the area.

Figure 5: Share of transactions with the top 5 trading partner countries: – commerce with services

Figure 5: Share of transactions with the top 5 trading partner countries: – commerce with goods

Figure 5: Share of transactions with the top 5 trading partner countries: – commerce with goodsAs we mentioned at the beginning of this analysis, Romania’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign direct investments (FDI) is particularly relevant for its strategic positioning within the global economy. At the same time, the statistical data show that companies benefiting from foreign direct investments have a major contribution to Romania’s international trade. For example, according to the information extracted from the statistical research “Foreign Investments in Romania in the year 2022” published by the National Bank of Romania, during the last year, FDI beneficiary companies exported goods worth 60.9 billion euros (71.3 percent of total exports) while their exports reached 76.6 billion euros (66.3 percent of total imports). At the same time, they achieved a surplus in services trade of approximately 9.9 billion euros (exports of 21.1 billion euros, imports of 11.2 billion euros).

In the region, the data show that, although not the largest economy, Hungary is currently the most attractive destination for foreign investors, surpassing Poland in terms of value of the stock of foreign direct investment, even if in its case the volatility of this indicator has been quite high in recent years.

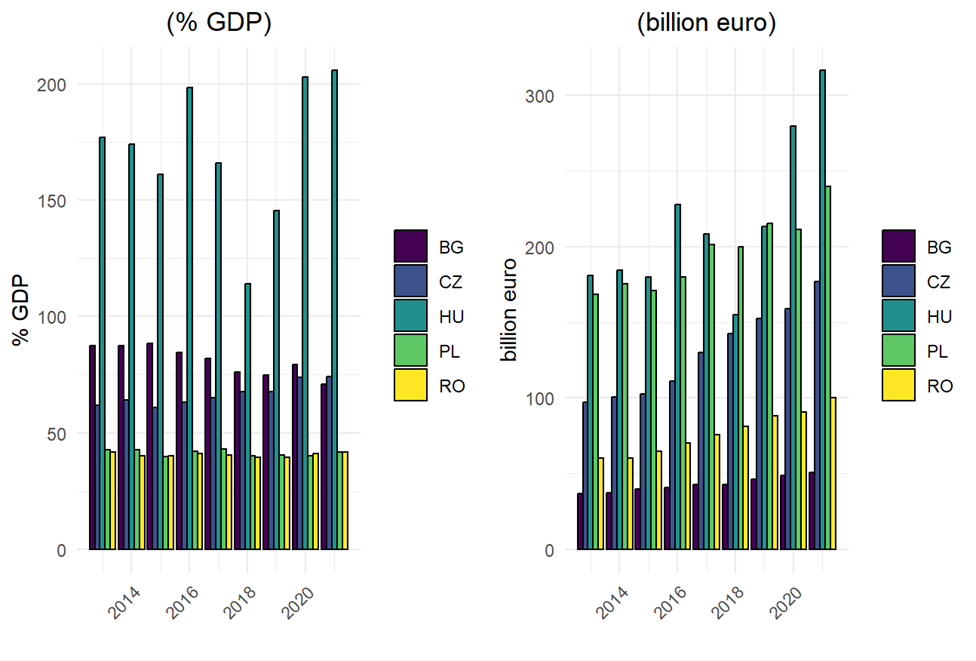

In the case of Romania, although the net flows of foreign direct investments have increased significantly in recent years, and their stock exceeded the threshold of 100 billion euros in 2021, this value still places us at a great distance behind Hungary, Poland, but also the Czech Republic. In relative terms, relative to GDP, the stock of FDI is comparable to that of Poland, but significantly lower than that of Bulgaria and the Czech Republic, and well behind Hungary. At the same time, it is observed that in the case of Romania and Poland, the ratio between FDI and GDP remained stable over the entire period 2013-2021, around the level of 41 percent, in the Czech Republic it increased from about 61 percent to about 74 percent, and in Bulgaria it decreased slightly, from 87 percent to 71 percent. According to Eurostat, in Hungary, the ratio between the stock of foreign direct investments and GDP was in 2021 over 205 percent.

Figure 6: Evolution of the stock of foreign direct investments

If we narrow the comparison to Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Romania (excluding Poland, with a much larger economy and Bulgaria with a significantly lower nominal GDP compared to Romania), we notice that, over time, both neighboring countries have managed to attract and maintain a stock of foreign investments significantly higher than Romania, both in nominal terms and in relation to GDP. A relevant observation in this regard would also be that in 2021, when the stock of foreign

direct investments in Romania exceeded 100 billion euros, basically it barely exceeded the level that the Czech Republic had already recorded seven years ago, in 2014.

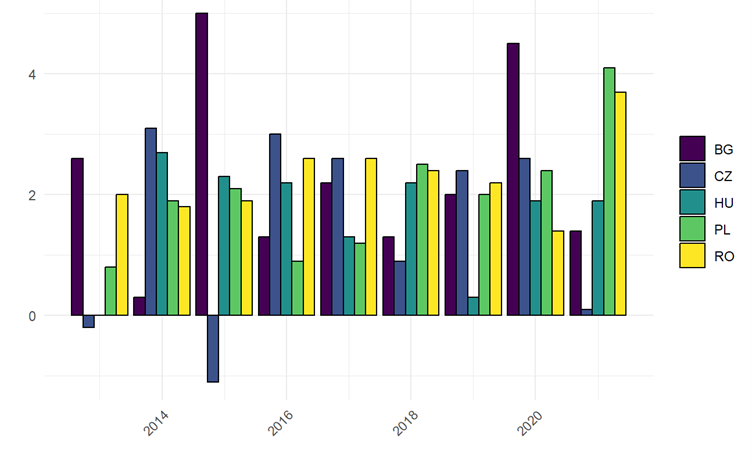

If we try to explain these differences from the perspective of annual flows, we notice that in this case too we are in the presence of a gap that comes largely from the past, from the period before the global financial crisis and before Romania’s accession to the European Union. Figure 7 below shows that in the period 2013 – 2021, FDI flows relative to GDP showed quite high volatility in the case of all the countries mentioned, without clearly highlighting a regional leader with a net superior performance in attracting FDI, given the size of their own economy.

Figure 7: Net foreign direct investment flows (% GDP)

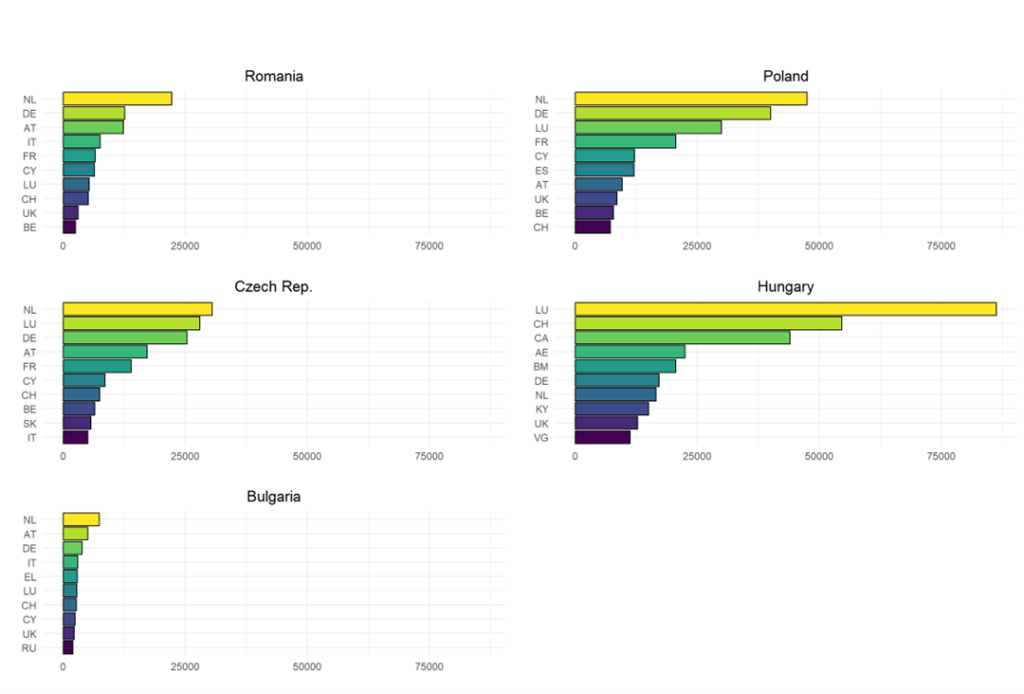

It is useful to look at the differences observed across countries in the region in terms of the stock of foreign direct investment and from the perspective of the investors’ country of origin. Because from the perspective of the final indicator on the Eurostat website, only the data for Romania and the Czech Republic are available for now, I have presented below the comparative situation according to the criterion of the immediate investor.

Figure 8: Distribution of the FDI stock in 2021 according to the country of the immediate investor (million euros)

We notice that the structure is relatively similar in the case of Poland, Romania, the Czech Republic, and Bulgaria, each time among the first four countries in the ranking being the Netherlands and Germany, in many cases Austria and France or Italy. Luxembourg also appears in the top four countries of origin for the Czech Republic and Poland, but not in the first position. However, in the case of Hungary, the country with the largest stock of FDI in the region (both in terms of value and share in GDP), a different picture can be observed: Luxembourg ranks first at a significant distance from the second place held by Switzerland, followed by Canada and the United Arab Emirates. Jurisdictions preferred by investment funds, such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, and the Virgin Islands, also occupy important places in the ranking of the top 10 countries of origin of foreign investors in Hungary.

The comparative analysis with neighboring countries highlights the areas in which Romania is adequately placed, but especially the areas in which it can further strengthen its economic competitiveness, studying the successes of better-positioned countries. The data from the trade balance for the first 7 months of 2023 show, for example, that Romania obtains a significant surplus on the IT services and transport side, but marks considerable deficits in trade of goods from the categories below:

- medical and pharmaceutical products (-2282 million euros),

- threads, fabrics, and related articles (-837 million euros),

- vegetables and fruits (-1240 million euros),

- meat and meat products (-627 million euros),

- dairy products and eggs (-436 million, euros),

- machines and equipment for transport (-1030 million euros),

- plastic materials in primary forms (-1043 million euros),

- oil, oil products, and related products (-2448 million euros),

In many of these areas, there is certainly local potential and the primary resources required for production, and the logistics costs for local distribution would certainly be lower than those for imports. Even if the problems related to the availability of skilled labor have indeed become important in recent years, they can be ameliorated if we persevere in correlating the education and training system with the priorities of the business environment. Also, certainly in all the above areas significant investments are needed to have a competitive local production, both in terms of cost and quality, but this should not represent such a difficult barrier, because we are going through a very beneficial period in terms of accessible funding sources, both through European programs and through foreign direct investments.

Concluding the short analysis above, Romania’s strategic positioning in the region from the perspective of exports and attracting foreign direct investments is a dynamic process that can be better channeled through a good understanding of the current situation and of the development potential. The challenges are significant, but the goal of reducing imbalances and moving the economy towards an increased presence in trade markets and as a destination for foreign investment justifies all the necessary efforts”.

acum 1 an

139

acum 1 an

139

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  Romanian (RO) ·

Romanian (RO) ·